My experience starting a pro-bono incubator for Italian student founders

The problem with the Italian startup ecosystem

When it comes to Italian startups, the conversation often revolves around how the ecosystem is lagging behind other European countries. This is usually accompanied by a chart like the one below, with a note on how many years it will take Italy to match France, Spain etc.

Oftentimes, many Italians that talk about the VC ecosystem add some polemical commentary on how Italian VCs don’t understand venture and what X and Y Italian institution and fund should do to match the X and Y institution and fund from another country.

When I started to pay more attention to these kinds of posts while living in the US some years ago, two things came to mind:

1. I realized that while it is important to measure where the market is compared to its peers and build a dialogue on what can be improved, this was more often than not done at the expense of a more constructive narrative.

Everyone commenting about something that doesn’t work, about whatever matter, on any social channel, should also offer his or her potential solution to the issue. Ideally, not what others should do, but what each one of us could do for the ecosystem.

There should be less conferences and workshops around startups and more action.

And I don’t think it’s enough to say ‘Italian VCs don’t have the balls to actually to their job, they should do more pre-seed and seed,’ etc. etc. I personally don’t blame Italian VCs. Anyone is free to have their own risk/reward appetite. Those who criticize Italian VCs for being more conservative should also praise them for not taking reckless bets that turn out very sour when the market turns.

2. Secondly, I started thinking that the problem with our startup ecosystem has deeper ramifications in our conservative culture, but also and most importantly in our education system.

The average entrepreneur in Italy is someone in their 30s, who has a good track record and money on the side to take a risk with his or her idea. Overall, Italian founders that receive funding are 8 years older than the European average.

This same entrepreneur is someone that might have been just as successful within their 20s, but who has been kept hostage of a system that forces you to focus all your energy on studying and getting a job.

The word school is derived from the Greek word schole, meaning ‘leisure.’ Yet our modern school system, born in the industrial revolution, has removed the leisure – and much of the pleasure – out of learning.

Students don’t approach university thinking about exploring different startups WHILE also studying. They simply cannot. There is the shadow of not graduating summa cum laude lurking on their backs.

They don’t have the peace of mind to build from scratch, because the peer pressure is so high and so the fear that you might miss the train to get a job at McKinsey or Amazon etc.

Generally speaking, our university system is the most disadvantageous for those who are the most curious: we ask an 18/ 19-year-old to decide what they want to study for the next 4 years without that much flexibility to mix disciplines.

We don’t give students the ability to explore but confine them into silos.

What’s wrong with letting someone explore for the first few years and then decide what to focus on? What’s wrong with wanting to build knowledge in computer science, business, and the classics?

We train them as if they needed those four years to become super high-skilled professionals in their field, as if there was a key, strategic position waiting for them upon graduation.

While I think our high school system is among the best in the world in the way it trains students, I think university often makes life harder for students to figure out their path, especially in entrepreneurship.

How Astra started

It was fall 2020, and while I didn’t have a solution for how to make our educational system more prone to boost entrepreneurship among students, I wanted to use my experience to help in some way.

Francesco, a former classmate from Berkeley had successfully launched a student-led pre-incubation program, and together with another fellow student from Cal and a couple from the Politecnico di Milano, they were working on designing something similar for the Italian market.

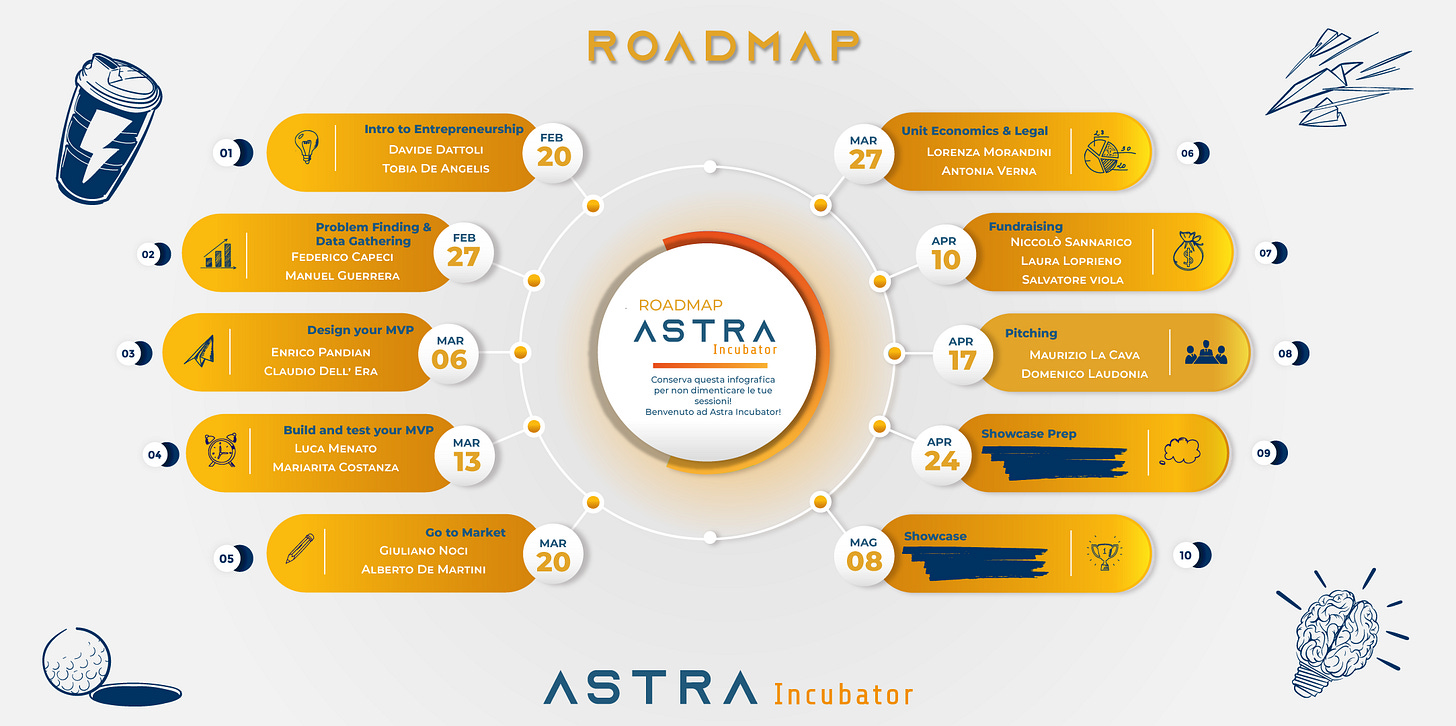

The program was called XIT Academy and the proposition was simple: a 10-week incubation program based on the lean startup approach, with weekly sessions on specific topics, guest speakers and a final pitch day in front of investors.

Aspiring founders with any background and skills could apply either with a formed team and an idea or as individuals. In the latter case, the program would match each founder with a team that was looking for those specific skills. They would, meet, chat, and decide themselves if they wanted to work together.

I decided to join forces with Francesco and team.

I thought that if we wanted to do something, we might as well give it a more aspirational name, and so we rebranded it to Astra.

I also thought that it made no sense to open the program to any kind of applicant.

When resources are limited (in our case, the resources were limited in terms of time and equal to naught in terms of budget), you need to be specific where you are going to spend them. The marginal benefits were higher if we focused on those who needed our help the most.

“Where is that we can be more impactful?” I thought. The answer was simple: I suggested to focus only on student founders that were at the very early phase of their startup journey.

Finally, to simply launch an incubation program was a naïve pursuit: first, because there are too many out there that have been doing it with way more resources.

Secondly, and most importantly, because while there is value in helping founders through a structured approach such as the lean startup one, we needed to have the ambition to aim higher and differentiate ourselves by adding more hands-on, practical value where it was most needed.

In the case of founders at their very first experience, that usually comes down to development, design skills, and growth marketing.

While the north star was to become something more akin to a venture studio, it was simply unrealistic to start with it, we simply lacked the resources.

However, even if we resolved to launch our first batch with a more traditional 10-week incubation program, we started testing from the very beginning offering specific help with development and design requests that came from the teams (more on this later).

As we set to embark on this journey, we didn’t write a mission nor a list of values etc.

Our goal was fairly simple: to help student founders go from 0 to 1 and possibly get them accepted into a vertically specialized incubator program or raise their first check.

Our values, were also straightforward: we all aligned on distancing ourselves from those self-proclaimed innovation platforms that profited from the inexperience of young founders, making them pay for resources they could easily get online or with the promise to help them with fundraising. Or those incubators/accelerators that give you cash for a certain % of equity but then ask you 50% back for the rent of the co-working space…

Astra was a 100% pro-bono program (i.e. we didn’t charge anything nor took any equity in the startups selected).

Batch 0

Given the pandemic, the fact that the program was remote gave us the chance to open the application to students from every school, from north to south. The team did a tremendous job setting up talks and workshops with student clubs to spread the message.

It was striking to see how many students outside the more conventional economics or engineering tracks were hesitant about participating. Students would wonder if they could apply even if they studied biology or philosophy, which again is telling about what the general mood students have when it comes to entrepreneurship in Italy.Once we opened the call, we were overwhelmed by the number of applications we received.

We interviewed ca. 50 teams out of the 400+ applications received and selected 20 of them.

We structured the program across 10 weeks following the lean startup approach.

In short, these were the main activities of the program:

Matching founders

As mentioned before, we would accept applications from teams but also individuals, and match the latter with teams looking for certain skills to complement the ones they already had. The founders would talk, see if they were a good match and if so start working together.

We did this before Y Combinator introduced it some 6 months later, and for this I give credit to Francesco for having the intuition that there is a lot of talent that can be developed, regardless of whether or not they have a team or an idea in mind already.

Content

Nowadays content is a commodity.

Founders don’t need more of it, if anything they need less, they need a structure to cut through the noise and get to what really matters to them. It’s not about teaching the stuff you could learn on Google, blogs, or podcasts; it’s about teaching the same stuff in 10% of the time, serving as a filter in terms of the content that actually matters, or just knowing what to teach yourself versus direct to other platforms for self-learning.

The challenge when dealing with first time founders, at least for me, is learning not to assume their level of knowledge: some concepts might be basic after you have seen 1000+ decks but it might not be so for someone who hears them for the first time.

Speakers and dedicated workshops

Every session had two speakers who brought their experience concerning a specific topic and to whom I’m extremely grateful for dedicating some of their time to this project (on a Saturday morning!!).

A note on this: one thing I learned is that oftentimes founders with a great track record (or an exit) are not necessarily the best teachers; founders who are under the radar, are sometimes not only more knowledgeable, but have also potentially gone through many more challenges, and are able to dissect those in a way that adds tangible value.

We also offered additional weekly workshops on dedicated topics based on the needs of our startups. For this first edition we organized a 4-hour workshop on omni-channel marketing and go-to-market strategies with an external agency and a 1.5-hour one covering legal aspects to keep in mind when setting up a startup.

Ad-hoc sessions with mentors and partners

We matched startups with relevant external partners and mentors as they faced specific issues.

Those ranged from SEO, legal and incorporation, UX/UI etc.

Some of these later turned into positive partnerships for both the partners/mentors.

A note on this: in the startup world there is not only a lot of noise in terms of content but also in terms of people: self-proclaimed innovators with a LinkedIn summary that usually reads as a long list of nouns such as ‘Innovator, Founder, Advisor, Leader, Coach, this and that who most of the time are all trying to sell you something, and that are often devoid of any practical skill.

It is still striking to see how many make a living with it. You learn pretty quickly how to dodge them.

Internal development and design team

We wanted to have the ambition to offer more practical help than a traditional incubation program.

In my opinion, Italian founders are not less talented, but are less practical and as such they need guided help, which at the early stage turns out to be development and design.

We were lucky to have these skills internally and tried to help startups on specific asks wherever we could. Or if we couldn’t we tried to connect the founders with some external partner.

Setting up a development/design team internally doesn’t happen overnight but it was a good pilot to iterate on.

Weekly coaching sessions with members of the team.

We met with founders on a weekly basis to check in on their progress and see where we could help by leveraging our own expertise and network.

These activities included brainstorming on strategy, customer research, product development, set up Facebook ads etc., making relevant connections with people in our network, and generally being a mentor (or a therapist, to some extent).

I was personally following 9 out of the 20 teams and putting aside some 10 hours per week only on this.

The rewarding thing is seeing how teams progress until they become more of an expert than you on specific topics.

Demo Day

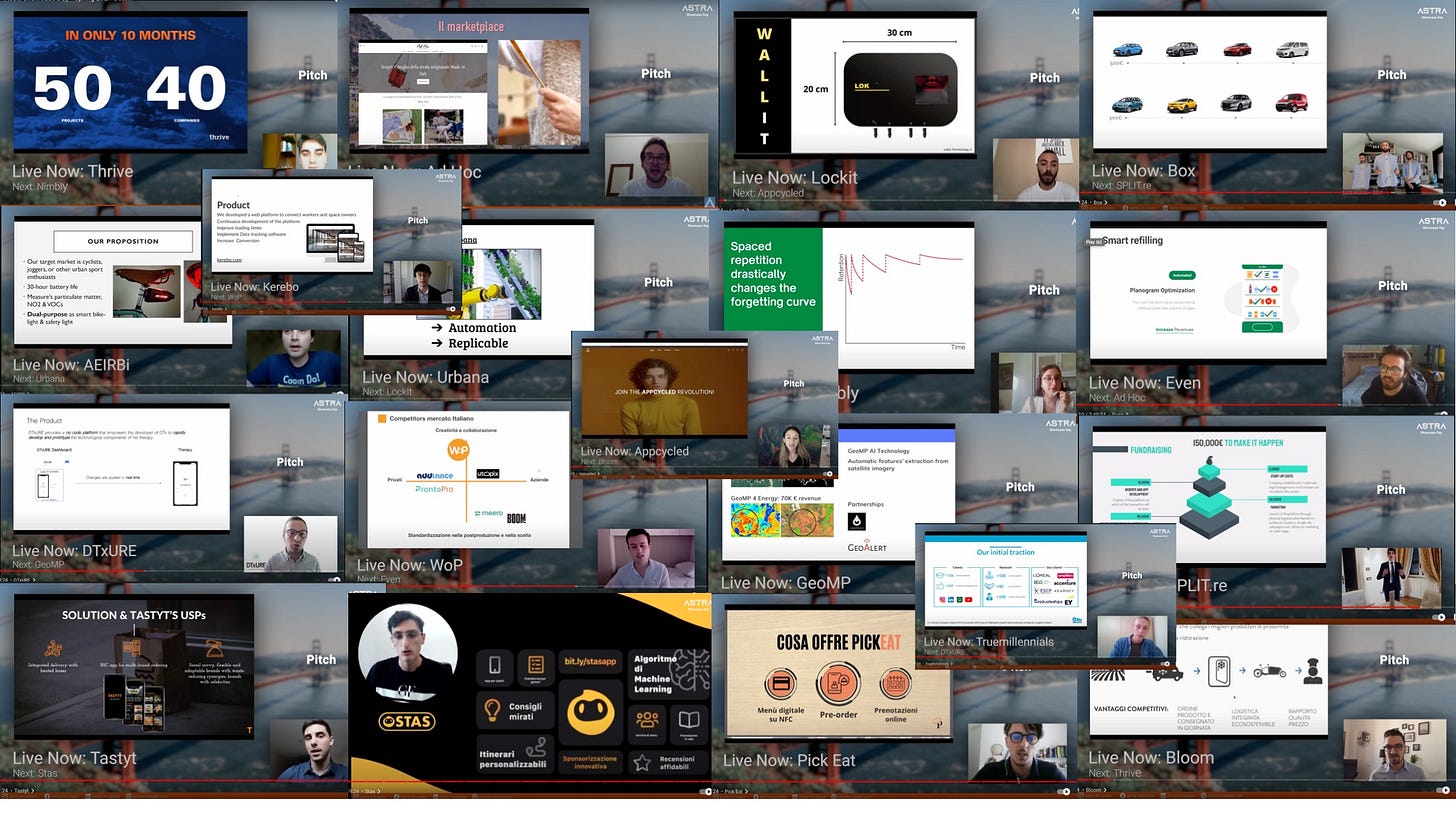

Finally, we concluded the batch with a showcase/demo day in May 2021, where our startups pitched their projects to an audience of stakeholders and investors (the recording is still available here).

The Ambition

To be honest, I personally couldn’t care less about creating just another incubator. There are too many, and unless you are Y Combinator, it’s a pretty shitty business.

As mentioned earlier, batch 0 was our MVP. Parallel to running the batch, we were also working on the second phase of Astra, that is, the evolution from an incubation program to a more tangible venture studio, based on the following pillars:

1. Italian founders are not less talented, but are less practical and as such they need guided help; even if incubation programs might bring some value, I think it doesn’t move the needle. Firstly, because there are too many, and secondly, because they don’t really address the needs of early stage founders, which are very practical: design, development, knowing how to run FB campaigns, knowing how to set up a quick MVP with Bubble etc.

Regardless of the name (incubator, accelerator, venture studio etc.), we wanted to be the most practical one-stop solution for student founders going from zero to one.

2. The fellowship program:

We didn’t want to reinvent the wheel but simply replicate the model implemented by Dorm Room Fund, Contrary Capital, and others, where they leverage students to act as scouts on campus to spot promising early stage founders and ideas.

Students are mentored and learn relevant ‘VC’ skills.

Win-Win.

3. Raise $1M to make small (€25-50K) direct investments into both the startups coming out of the studio and those sourced by the campus scouts.

Bringing in house designers, developers, growth hackers etc. is a massive endeavour and one we couldn’t possibly achieve by running the whole game as a pro-bono gig. Hard work and passion are unsustainable by themselves: we also needed a partner to support us and make our vision into a reality. At which stage we would have received an equity stake in the startup.

We needed to make this sustainable and build a solid foundation, and for this we needed resources.

We talked with lots of stakeholders, both private and public, but were mostly met with scepticism. Which to some extent I understand: incubators are, generally speaking, terrible businesses and we knew it from the very beginning. Moreover, none of us had an exit on our back to boast.

While very formative, this entire process was a bit exhausting for me, and at the end of the batch I decided not to pursue it any further.

I take no ownership in what has been done later with Astra or for what will come in the future.

Results

The only thing that matters when it comes to evaluating an incubator/accelerator is the tangible results the startups achieve afterwards.

13 months after the demo day, as I write this retrospective, 6/20 startups are still active and pursuing their project.

Of these:

- AdHoc has raised a pre-seed round, grown GMV to ca. €30K/month and successfully expanded into B2B. After the batch, the team asked me if I wanted to continue working with them as an advisor. It’s been a great journey in the past 16 months.

- Dootbox has launched it’s ‘Car as a service’ subscription platform, a virtual garage where clients can choose, lease and replace their car whenever they want, with no hidden fees. They took first place in the Polimi Start-up competition and won the Dealer Day Generation Award.

- Pick Eat has launched their restaurant pre-order app and have recently registered their first transactions.

- Mad Fresh has developed their own innovative vertical farming system and are about to build a second larger greenhouse. They are producing and selling strawberries and other vegetables and signed a distribution agreement with a national retailer.

Our goal with Astra was first and foremost to inspire founders to pursue their projects.

Considering that most of our startups were ideas on a piece of paper at the beginning of the program 18 months ago, I’m proud of these results.

I recently heard from a couple of founders, who went on to participate in more capitalized and renowned national accelerators, and mentioned that Astra turned out to be way more practical than those others.

Considering that this was a program run with zero budget (or €10, the price of the domain), I guess it’s a small win.

The remaining 14/20 startups have discontinued their project because of the usual suspects: lack of product market fit, lack of conviction, lack of funding.

However, what I found striking was also another reason that a few mentioned, that is, fear of missing out on a job opportunity. Not just from startups that were never really able to get off the ground, in which case it would totally be reasonable, but also from those who were generating revenues and had a promising traction.

Final Thoughts

I finally took the time to sit down 13 months after the end of our experiment to think about this experience.

Running a fully remote incubator across two time zones 9 hours apart was a massive endeavour. But it was also rewarding to learn from passionate young founders and try to connect the dots with them. I have learned a lot from them.

In retrospective, this might have been a naïve pursuit, but you need a touch of it to get anything started in life.

We have achieved this with only €10 in spend but with a lot of passion and hard work. We were able to give without asking from anybody, and to this I’m proud and grateful to the rest of the team, our partners and mentors for believing that we could make a small difference in this country.

I hope Astra will keep pursuing its goal to inspire student founders to start their own project.

How can the most inventive, creative country in the world lag so drastically behind in terms of startups? I’m sure that if we could find a metric such as ‘Creativity per capita,’ Italy would be among the top rankings.

As mentioned at the beginning, I strongly believe our startup problem is one that lies not only in our conservative culture but most importantly within our education system.

People like Prof. Daniele Manni, who won the Global Teacher Prize in 2021 for his innovative teaching methods at his high school in the south of Italy, are examples of the kind of structural change that is needed to make it possible for our startup ecosystem to catch up with the rest of the world.